I decided that rather than try to describe what my vision has been and currently is, I would post some images. You may find this hard to beliee, but these images are not from a biology textbook; I drew them myself.

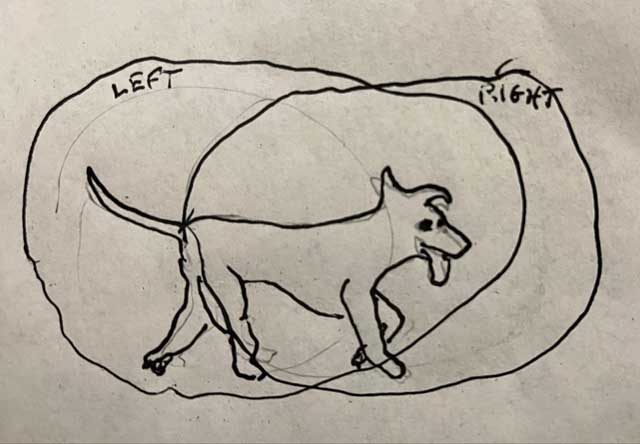

First, this is what normal vision (sort of) looks like:

Each of your eyes see its own image of this odd-looking dog with the odd-looking gait. They are slightly different, but your brain seamlessly merges them into one coherent image. You are normally not aware that there are two separate images in the overlapping area, but the differences in the images are what allows you to perceive the different distances to various objects that you see.

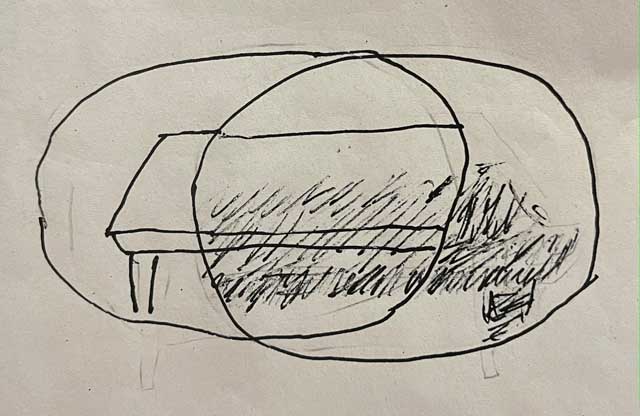

After my surgery, the vitreous in my right eye was replaced with sulfur hexafluoride (SF6). The optical properties of SF6 are different from that of the vitreous, and the eye can’t focus an image through it. That means that my right eye’s image was blurry, and objects in my field of view seemed to be in a different place from what my left eye was reporting. This yielded an image kind of like this:

Imagine that I was looking at a table. My left eye saw it clearly, while my right eye saw a blurry, displaced images. My brain couldn’t figure out how to merge these images, so it basically didn’t. It just gave me two different images at the same time. This made it essentially impossible to read or to drive. Since I spent Thursday afternoon after the surgery through Sunday with my head down, reading was about all I could do. I solved this problem by closing my right eye.

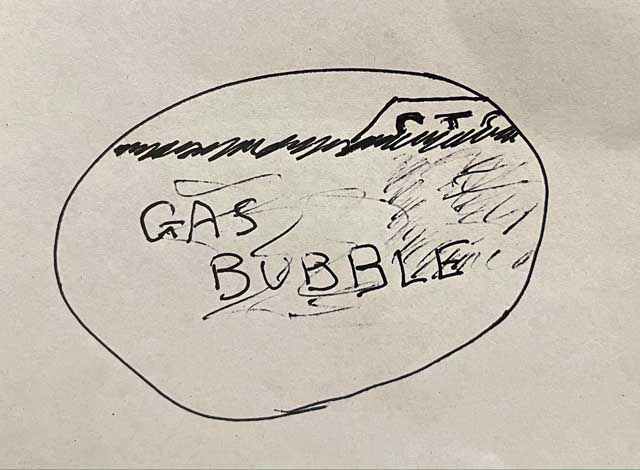

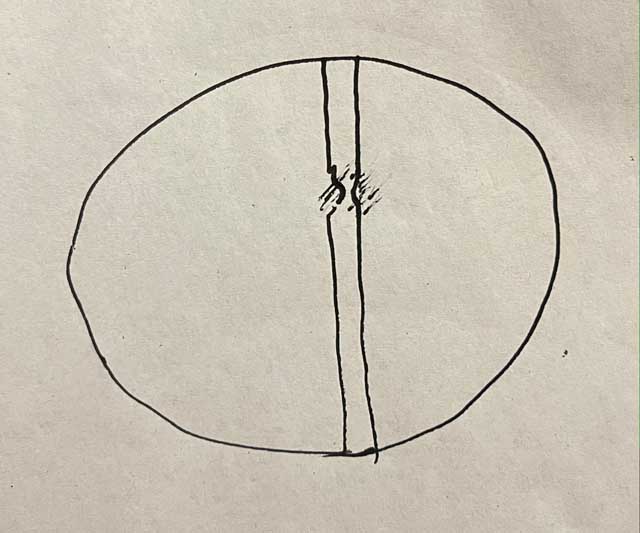

As the body absorbed the SF6, the bubble shrank. For several days, this is what I saw with my right eye:

The very top of my visual field was clear, while all of the rest was blurry. There was not enough clear vision to allow my eye to focus at normal distances, so I still had to close my right eye to read, and I couldn’t drive.

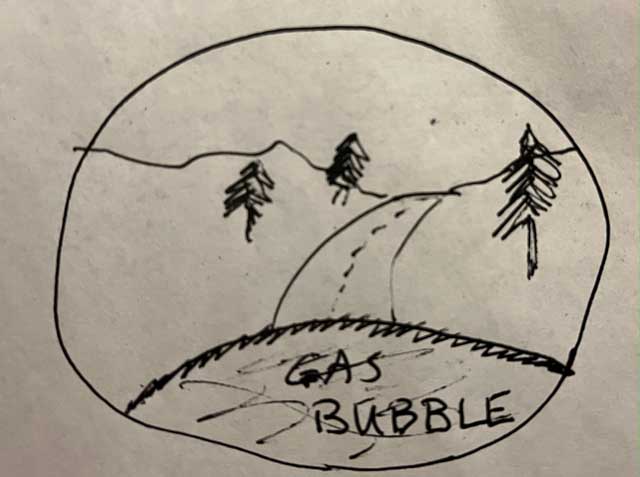

Eventually, the bubble shrank to the point that it was beneath almost everything I needed to see, leaving something like this:

This image is from what I imagine driving though the foothills of the Sierras would look like.

And this is what my vision is like as I write this on Saturday night. I can look up where I’m writing and can see the mess of objects on our dining table, and, most importantly, i can tell where they are. I can reach out and touch the salt shaker without making several tries. Unfortunately, if I look down, I am looking through the bubble and I have no depth perception. A Walmart employee had to help me put my credit card in the reader tonight because I kept missing the slot

If I look straight down, I can see the entire bubble as a circle filling maybe 80 percent of the entire field of view. The bubble jiggles when I shake my head, like a bowl of Jello. When I look up, the bubble reminds me of the bubble in a spirit level, finding its own level as I move my head around.

But, you are wondering, if this is a gas bubble within an eyeball otherwise filled with fluid, why is it floating at the bottom of my eye rather than the top? That’s an astute question, and I’m glad you asked. I wondered about that myself for a while, and then I remembered that the image the eye’s lens projects on the back of the eye is inverted; it’s upside down. The brain perceives it as right-side-up. Since the bubble is at the top of an upside down image, the brain thinks the bubble is actually at the bottom of my eye, thus fooling both itself and me.

Since I am still recuperating, I continue to spend a lot of time reading on my phone. Looking down still moves my bubble up (actually, down) into my field of view, so it’s still a real distraction. My solution now is to put blue masking tape on the right lens of a cheap pair of reading glasses.

I can still see the bubble in my right eye; in fact, in a lighted room, I can see the bubble with both eyes closed. But I can do a pretty good job of ignoring it. Right now there is a ghost image of the bubble covering about the bottom third of my laptop’s screen. It’s somewhat distracting, but much less than it would be without masking tape on my glasses.

There is one discouraging development. At my post-op appointment, while waiting for the doctor to come into the examination room, I discovered that I could focus on an object very close to my eye. I put a medical alert bracelet I was wearing up close and could read the fine print. It seemed to me that the blind spot and distortion I had been experiencing were gone. That made me very happy. Unfortunately, I have since determined that I still have a blind spot and distortion at my fovea. If I look at a straight line, I see something like this:

The images is blurred and distorted, and whatever is at the very center of the fovea is not visible. If I look directly at a small object, it disappears and is replaced by whatever surrounds it in my visual field. A small stone on a concrete surface disappears, and where it should be looks like more concrete. The effect might not be quite as bad as before my surgery, but it’s still there.

I have read that one’s vision after a vitrectomy can continue to improve for up to six months, so maybe it will get better. If it doesn’t, I suppose, and hope, that my brain will accomodate that deficiency and begin to ignore the blurring and distortion, replacing it with the better image from my left eye.